You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

In this feature, we share Slow Living LDN. founder Beth’s inspiring conversation with Tom Calver, director of Westcombe Dairy in Somerset.

Deep in the Somerset countryside lies Westcombe Dairy, a family-run business producing raw milk cheese with character. The concept of terroir is at the heart of the Westcombe story, and describes the influence of the local area’s unique geography and environment on the food and drink produced there. The area’s lush pastures for grazing dairy cows create rich milk and flavoursome cheese. Westcombe Dairy produces one of only three cheddars recognised by Slow Food as part of the Artisanal Somerset Cheddar Presidium.

On a warm summer’s afternoon, I winded down country lanes to find Westcombe Farm, nestled amongst some of Somerset’s finest scenery. After a warm welcome from Tom, Westcombe’s director, I keenly accepted the offer of a tour around the farm. We piled into his Land Rover and toured the lanes and fields, making a pitstop to hear his vision for a crumbling yet beautiful farmhouse that is to be renovated. Outside, we spent a few moments admiring Tom’s wife Mel’s cutting garden and growing shed, which supplies the flowers for her new floral venture, Re-Rooting.

Westcombe Farm has a history of making unpasteurised cheddar dating back as early as 1890, first by renowned cheesemaker Edith Cannon and later by Mr and Mrs Brickell. Tom explained how the business grew as Westcombe created alliances with other local farms and that, after World War II, the cheesemaking industry underwent great centralisation. Today, less than 5% of the 400 producers who once made cheddar in Somerset remain in business.

In the 1960s, Tom’s father, Richard Calver, joined the business as a partner and greatly improved the condition of the farm’s pastureland and the quality of the milk being produced. By the 1970s, demand increased for rindless, pasteurised block cheddar. Tom shared how Westcombe followed suit for a while, but later decided to return to its roots of raw milk cheeses. Since Tom joined the family business in 2008 after learning the ropes at Neal’s Yard Dairy in London, he’s been on a quest to create the highest quality cheese, enhanced by the area’s terroir. Today, Westcombe produces traditional unpasteurised cheddar aged for 12 to 18 months; ricotta, aged Caerphilly, Westcombe red, smoked cheddar and Lamyatt, a mild alpine-style mountain cheese.

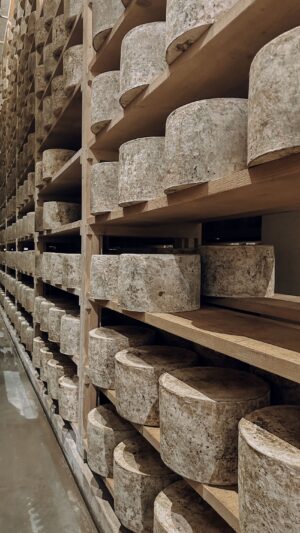

After returning to the dairy, we visited the cheese cave. Inside the temperature controlled space, which is carved into the Somerset hillside, shelves of cheese wheels are lined up from floor to ceiling. It’s quite a sight to behold. It’s also the home to ‘Tina the Turner’, Westcombe’s state of the art robot, who tirelessly turns the cheeses to keep moisture in check and mould controlled. It is a beautiful example of how technology can strengthen traditional, slow techniques.

With the tour complete we sat down and continued our conversation over a cup of tea in Tom’s rustic kitchen. Despite achieving slow food status, Tom dispels the whimsical notion that he and his team are serenely “floating around the dairy”. Quite the opposite. The art of traditional cheesemaking is hard work. Yet there’s no doubt Tom’s passion for perfecting his product and championing more holistic management of food systems outweighs the graft required.

In addition to cheese, Westcombe has expanded into charcuterie, making use of their home-reared bull calves and ensuring a more sustainable use of their overall herd. He envisions a future with more interconnected enterprises at Westcombe, to join the handful of likeminded businesses already in residency. This includes Bath’s popular Landrace Bakery and bijoux restaurant ‘Upstairs’, who mill their flour onsite, and Woodshedding Brewery, who welcome visitors to their beer hall at the farm on Thursdays and Fridays.

In conversation with Tom Calver, Westcombe Dairy

Can you walk me through the slower cheesemaking processes you adopt at Westcombe? How does this differ from the mainstream process?

Tom: “There was a period in the eighties when testing for different pathogens became more efficient. One of the ways people tried to produce safer food was to increase the amount of starter culture which shortened the overall process to four hours, or maybe three hours and 50 minutes.

The problem we found when we started out making cheese using these modern, faster methods was that if you shorten the process you’re giving less time to extract moisture. We found that if we make the process a lot slower – we’re up to more like five and a half to six hours – we can create so much more body and a better texture.

If you’re looking for volume, then the speed has to be so much quicker. If you’ve got half a million litres of milk waiting to go through a system, you just get it done as fast as possible. Whereas when we’re doing stuff at this scale, which is a lot smaller at just one vat per day, we can allow this very natural process to express itself in its own unique way. When you’re making raw milk cheese you have to let everything express itself, otherwise what’s the point in doing it?”

What are you trying to achieve at Westcombe with your raw milk cheeses?

Tom: “We’re trying to communicate the joy of this cheese. Who wants to have consistency? How boring is that? We did start off getting really worried about consistency. But then you take a step back and think, we can inspire a cheesemonger on the high street with our cheese. After all, what are their stresses and hassles? They’ve got supermarkets right on their doorstep that they’re fighting against so they need to differentiate. How can we provide something that’s got character and uniqueness that helps them engage so much more with their customer base?

It’s difficult to reinvent a very old school cheddar and get people consistently excited about it, especially in the UK, because with food, we can be quite fickle. We’ve had a lot of influence from so many other countries throughout history, but actually, the stuff that we make in the UK and are good at, sometimes gets forgotten.”

What does regenerative farming mean to you?

Tom: “I think it’s to regenerate the land. You’re actually looking at the system to try and build the soil rather than constantly take away from it.

There’s a big debate about whether or not you should have some kind of rules or framework around regenerative, and I don’t really know. I quite like the idea that there’s no framework because then, in theory, I hope people will ask why their farmers are using the term regenerative and then people can make their own mind up.

The problem is sometimes when you put rules around something, then the rules can be exploited, and then that will lose its value again. So, for me, regenerative is trying to rebuild and look at your farming system more holistically, rather than growing monocultures.”

What can we do to raise awareness of slow food and artisan producers?

Tom: “Conscious consumption and teaching your kids. That’s probably the most important thing. Just getting your kids out in the soil and getting them to grow stuff. Getting everybody to grow stuff, not just the kids, the adults as well. Then you’ll actually feel some kind of empathy with your food producers and what they have to do, because it’s tough.

I think it’s about understanding the people who produce your food, what it is that you’re consuming, and what the moral dynamics are that those particular businesses are facing. It’s okay to consume certain foods but make sure you’ve got your eyes open and know your food’s story.

With the charcuterie side of things, we’re trying to make lard a thing again and I think the timing is right. If people really knew the whole story behind some of the unnatural chemical processes used to make hydrogenated fats (as seen in margarine, fast food, commercial baked goods, processed foods), then maybe they would start to think about certain things in a different way. For example, Carina in the shop has been making some absolutely insanely beautiful pastries by just using lard as a substitute for butter.

Lastly, if you’re going to consume anything, you have to consume all of it. Don’t just go for a fillet steak, get excited about any other part of the animal (like lard) because it’s all got its own unique flavour. It all has to be consumed, otherwise you’re just taking the cream off the top and wasting the rest.”

What does the future hold for Westcombe?

Tom: “One of the exciting things that’s happened over the past few years – thanks to having many different enterprises in close proximity to one and other – is you find one enterprise’s waste product is another’s raw ingredient. It makes for a very complicated life and a very complicated business, because you’ve got a lot of moving parts, but it can create really interesting relationships and a lot of empathy and understanding within a whole structural food system, as well. Hopefully, as we evolve, we can find more people who are interested in supplying us in that particular way.”

Are you particular in the way you consume your cheese or do you use it in everyday cooking?

Tom: “I’m not a purist. I think a purist is to cook with everything. There’s no such thing as too good for cooking because if you want to produce the best meal ever, then start off with some decent ingredients. I would really encourage people to use products like ours in cooking because it makes it so much more of a joy.”

To find out more about Tom, the farm and the growing small business community onsite, you can visit Westcombe Dairy. You can also buy cheese directly from Westcombe Dairy online. Or, you can find them at local markets such as the Frome Independent and stocked by a large number of cheesemongers and farm shops across the country.